Branch of soil physics and applied mechanics that describes the behavior of soils

The Leaning Tower of Pisa – an example of a problem due to deformation of soil

The Leaning Tower of Pisa – an example of a problem due to deformation of soil

Slope instability issues for a temporary flood control levee in North Dakota, 2009

Slope instability issues for a temporary flood control levee in North Dakota, 2009

Earthwork in Germany

Earthwork in Germany

Fox Glacier, New Zealand: Soil produced and transported by intense weathering and erosion

Fox Glacier, New Zealand: Soil produced and transported by intense weathering and erosion

Soil mechanics is a branch of soil physics and applied mechanics that describes the behavior of soils. It differs from fluid mechanics and solid mechanics in the sense that soils consist of a heterogeneous mixture of fluids (usually air and water) and particles (usually clay, silt, sand, and gravel) but soil may also contain organic solids and other matter.[1][2][3][4] Along with rock mechanics, soil mechanics provides the theoretical basis for analysis in geotechnical engineering,[5] a subdiscipline of civil engineering, and engineering geology, a subdiscipline of geology. Soil mechanics is used to analyze the deformations of and flow of fluids within natural and man-made structures that are supported on or made of soil, or structures that are buried in soils.[6] Example applications are building and bridge foundations, retaining walls, dams, and buried pipeline systems. Principles of soil mechanics are also used in related disciplines such as geophysical engineering, coastal engineering, agricultural engineering, and hydrology.

This article describes the genesis and composition of soil, the distinction between pore water pressure and inter-granular effective stress, capillary action of fluids in the soil pore spaces, soil classification, seepage and permeability, time dependent change of volume due to squeezing water out of tiny pore spaces, also known as consolidation, shear strength and stiffness of soils. The shear strength of soils is primarily derived from friction between the particles and interlocking, which are very sensitive to the effective stress.[7][6] The article concludes with some examples of applications of the principles of soil mechanics such as slope stability, lateral earth pressure on retaining walls, and bearing capacity of foundations.

Genesis and composition of soils

[edit]

Genesis

[edit]

The primary mechanism of soil creation is the weathering of rock. All rock types (igneous rock, metamorphic rock and sedimentary rock) may be broken down into small particles to create soil. Weathering mechanisms are physical weathering, chemical weathering, and biological weathering [1][2][3] Human activities such as excavation, blasting, and waste disposal, may also create soil. Over geologic time, deeply buried soils may be altered by pressure and temperature to become metamorphic or sedimentary rock, and if melted and solidified again, they would complete the geologic cycle by becoming igneous rock.[3]

Physical weathering includes temperature effects, freeze and thaw of water in cracks, rain, wind, impact and other mechanisms. Chemical weathering includes dissolution of matter composing a rock and precipitation in the form of another mineral. Clay minerals, for example can be formed by weathering of feldspar, which is the most common mineral present in igneous rock.

The most common mineral constituent of silt and sand is quartz, also called silica, which has the chemical name silicon dioxide. The reason that feldspar is most common in rocks but silica is more prevalent in soils is that feldspar is much more soluble than silica.

Silt, Sand, and Gravel are basically little pieces of broken rocks.

According to the Unified Soil Classification System, silt particle sizes are in the range of 0.002 mm to 0.075 mm and sand particles have sizes in the range of 0.075 mm to 4.75 mm.

Gravel particles are broken pieces of rock in the size range 4.75 mm to 100 mm. Particles larger than gravel are called cobbles and boulders.[1][2]

Transport

[edit]

Example soil horizons. a) top soil and colluvium b) mature residual soil c) young residual soil d) weathered rock

Example soil horizons. a) top soil and colluvium b) mature residual soil c) young residual soil d) weathered rock

Soil deposits are affected by the mechanism of transport and deposition to their location. Soils that are not transported are called residual soils—they exist at the same location as the rock from which they were generated. Decomposed granite is a common example of a residual soil. The common mechanisms of transport are the actions of gravity, ice, water, and wind. Wind blown soils include dune sands and loess. Water carries particles of different size depending on the speed of the water, thus soils transported by water are graded according to their size. Silt and clay may settle out in a lake, and gravel and sand collect at the bottom of a river bed. Wind blown soil deposits (aeolian soils) also tend to be sorted according to their grain size. Erosion at the base of glaciers is powerful enough to pick up large rocks and boulders as well as soil; soils dropped by melting ice can be a well graded mixture of widely varying particle sizes. Gravity on its own may also carry particles down from the top of a mountain to make a pile of soil and boulders at the base; soil deposits transported by gravity are called colluvium.[1][2]

The mechanism of transport also has a major effect on the particle shape. For example, low velocity grinding in a river bed will produce rounded particles. Freshly fractured colluvium particles often have a very angular shape.

Soil composition

[edit]

Soil mineralogy

[edit]

Silts, sands and gravels are classified by their size, and hence they may consist of a variety of minerals. Owing to the stability of quartz compared to other rock minerals, quartz is the most common constituent of sand and silt. Mica, and feldspar are other common minerals present in sands and silts.[1] The mineral constituents of gravel may be more similar to that of the parent rock.

The common clay minerals are montmorillonite or smectite, illite, and kaolinite or kaolin. These minerals tend to form in sheet or plate like structures, with length typically ranging between 10−7 m and 4x10−6 m and thickness typically ranging between 10−9 m and 2x10−6 m, and they have a relatively large specific surface area. The specific surface area (SSA) is defined as the ratio of the surface area of particles to the mass of the particles. Clay minerals typically have specific surface areas in the range of 10 to 1,000 square meters per gram of solid.[3] Due to the large surface area available for chemical, electrostatic, and van der Waals interaction, the mechanical behavior of clay minerals is very sensitive to the amount of pore fluid available and the type and amount of dissolved ions in the pore fluid.[1]

The minerals of soils are predominantly formed by atoms of oxygen, silicon, hydrogen, and aluminum, organized in various crystalline forms. These elements along with calcium, sodium, potassium, magnesium, and carbon constitute over 99 per cent of the solid mass of soils.[1]

Grain size distribution

[edit]

Main article: Soil gradation

Soils consist of a mixture of particles of different size, shape and mineralogy. Because the size of the particles obviously has a significant effect on the soil behavior, the grain size and grain size distribution are used to classify soils. The grain size distribution describes the relative proportions of particles of various sizes. The grain size is often visualized in a cumulative distribution graph which, for example, plots the percentage of particles finer than a given size as a function of size. The median grain size,  , is the size for which 50% of the particle mass consists of finer particles. Soil behavior, especially the hydraulic conductivity, tends to be dominated by the smaller particles, hence, the term "effective size", denoted by

, is the size for which 50% of the particle mass consists of finer particles. Soil behavior, especially the hydraulic conductivity, tends to be dominated by the smaller particles, hence, the term "effective size", denoted by  , is defined as the size for which 10% of the particle mass consists of finer particles.

, is defined as the size for which 10% of the particle mass consists of finer particles.

Sands and gravels that possess a wide range of particle sizes with a smooth distribution of particle sizes are called well graded soils. If the soil particles in a sample are predominantly in a relatively narrow range of sizes, the sample is uniformly graded. If a soil sample has distinct gaps in the gradation curve, e.g., a mixture of gravel and fine sand, with no coarse sand, the sample may be gap graded. Uniformly graded and gap graded soils are both considered to be poorly graded. There are many methods for measuring particle-size distribution. The two traditional methods are sieve analysis and hydrometer analysis.

Sieve analysis

[edit]

Sieve

Sieve

The size distribution of gravel and sand particles are typically measured using sieve analysis. The formal procedure is described in ASTM D6913-04(2009).[8] A stack of sieves with accurately dimensioned holes between a mesh of wires is used to separate the particles into size bins. A known volume of dried soil, with clods broken down to individual particles, is put into the top of a stack of sieves arranged from coarse to fine. The stack of sieves is shaken for a standard period of time so that the particles are sorted into size bins. This method works reasonably well for particles in the sand and gravel size range. Fine particles tend to stick to each other, and hence the sieving process is not an effective method. If there are a lot of fines (silt and clay) present in the soil it may be necessary to run water through the sieves to wash the coarse particles and clods through.

A variety of sieve sizes are available. The boundary between sand and silt is arbitrary. According to the Unified Soil Classification System, a #4 sieve (4 openings per inch) having 4.75 mm opening size separates sand from gravel and a #200 sieve with an 0.075 mm opening separates sand from silt and clay. According to the British standard, 0.063 mm is the boundary between sand and silt, and 2 mm is the boundary between sand and gravel.[3]

Hydrometer analysis

[edit]

The classification of fine-grained soils, i.e., soils that are finer than sand, is determined primarily by their Atterberg limits, not by their grain size. If it is important to determine the grain size distribution of fine-grained soils, the hydrometer test may be performed. In the hydrometer tests, the soil particles are mixed with water and shaken to produce a dilute suspension in a glass cylinder, and then the cylinder is left to sit. A hydrometer is used to measure the density of the suspension as a function of time. Clay particles may take several hours to settle past the depth of measurement of the hydrometer. Sand particles may take less than a second. Stokes' law provides the theoretical basis to calculate the relationship between sedimentation velocity and particle size. ASTM provides the detailed procedures for performing the Hydrometer test.

Clay particles can be sufficiently small that they never settle because they are kept in suspension by Brownian motion, in which case they may be classified as colloids.

Mass-volume relations

[edit]

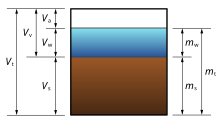

A phase diagram of soil indicating the masses and volumes of air, solid, water, and voids

A phase diagram of soil indicating the masses and volumes of air, solid, water, and voids

There are a variety of parameters used to describe the relative proportions of air, water and solid in a soil. This section defines these parameters and some of their interrelationships.[2][6] The basic notation is as follows:

,

,  , and

, and  represent the volumes of air, water and solids in a soil mixture;

represent the volumes of air, water and solids in a soil mixture;

,

,  , and

, and  represent the weights of air, water and solids in a soil mixture;

represent the weights of air, water and solids in a soil mixture;

,

,  , and

, and  represent the masses of air, water and solids in a soil mixture;

represent the masses of air, water and solids in a soil mixture;

,

,  , and

, and  represent the densities of the constituents (air, water and solids) in a soil mixture;

represent the densities of the constituents (air, water and solids) in a soil mixture;

Note that the weights, W, can be obtained by multiplying the mass, M, by the acceleration due to gravity, g; e.g.,

Specific Gravity is the ratio of the density of one material compared to the density of pure water ( ).

).

Specific gravity of solids,

Note that specific weight, conventionally denoted by the symbol  may be obtained by multiplying the density (

may be obtained by multiplying the density (  ) of a material by the acceleration due to gravity,

) of a material by the acceleration due to gravity,  .

.

Density, bulk density, or wet density,  , are different names for the density of the mixture, i.e., the total mass of air, water, solids divided by the total volume of air water and solids (the mass of air is assumed to be zero for practical purposes):

, are different names for the density of the mixture, i.e., the total mass of air, water, solids divided by the total volume of air water and solids (the mass of air is assumed to be zero for practical purposes):

Dry density,  , is the mass of solids divided by the total volume of air water and solids:

, is the mass of solids divided by the total volume of air water and solids:

Buoyant density,  , defined as the density of the mixture minus the density of water is useful if the soil is submerged under water:

, defined as the density of the mixture minus the density of water is useful if the soil is submerged under water:

where  is the density of water

is the density of water

Water content,  is the ratio of mass of water to mass of solid. It is easily measured by weighing a sample of the soil, drying it out in an oven and re-weighing. Standard procedures are described by ASTM.

is the ratio of mass of water to mass of solid. It is easily measured by weighing a sample of the soil, drying it out in an oven and re-weighing. Standard procedures are described by ASTM.

Void ratio,  , is the ratio of the volume of voids to the volume of solids:

, is the ratio of the volume of voids to the volume of solids:

Porosity,  , is the ratio of volume of voids to the total volume, and is related to the void ratio:

, is the ratio of volume of voids to the total volume, and is related to the void ratio:

Degree of saturation,  , is the ratio of the volume of water to the volume of voids:

, is the ratio of the volume of water to the volume of voids:

From the above definitions, some useful relationships can be derived by use of basic algebra.

Soil classification

[edit]

Geotechnical engineers classify the soil particle types by performing tests on disturbed (dried, passed through sieves, and remolded) samples of the soil. This provides information about the characteristics of the soil grains themselves. Classification of the types of grains present in a soil does not[clarification needed] account for important effects of the structure or fabric of the soil, terms that describe compactness of the particles and patterns in the arrangement of particles in a load carrying framework as well as the pore size and pore fluid distributions. Engineering geologists also classify soils based on their genesis and depositional history.

Classification of soil grains

[edit]

In the US and other countries, the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS) is often used for soil classification. Other classification systems include the British Standard BS 5930 and the AASHTO soil classification system.[3]

Classification of sands and gravels

[edit]

In the USCS, gravels (given the symbol G) and sands (given the symbol S) are classified according to their grain size distribution. For the USCS, gravels may be given the classification symbol GW (well-graded gravel), GP (poorly graded gravel), GM (gravel with a large amount of silt), or GC (gravel with a large amount of clay). Likewise sands may be classified as being SW, SP, SM or SC. Sands and gravels with a small but non-negligible amount of fines (5–12%) may be given a dual classification such as SW-SC.

Atterberg limits

[edit]

Clays and Silts, often called 'fine-grained soils', are classified according to their Atterberg limits; the most commonly used Atterberg limits are the liquid limit (denoted by LL or  ), plastic limit (denoted by PL or

), plastic limit (denoted by PL or  ), and shrinkage limit (denoted by SL).

), and shrinkage limit (denoted by SL).

The liquid limit is the water content at which the soil behavior transitions from a plastic solid to a liquid. The plastic limit is the water content at which the soil behavior transitions from that of a plastic solid to a brittle solid. The Shrinkage Limit corresponds to a water content below which the soil will not shrink as it dries. The consistency of fine grained soil varies in proportional to the water content in a soil.

As the transitions from one state to another are gradual, the tests have adopted arbitrary definitions to determine the boundaries of the states. The liquid limit is determined by measuring the water content for which a groove closes after 25 blows in a standard test.[9][clarification needed] Alternatively, a fall cone test apparatus may be used to measure the liquid limit. The undrained shear strength of remolded soil at the liquid limit is approximately 2 kPa.[4][10] The plastic limit is the water content below which it is not possible to roll by hand the soil into 3 mm diameter cylinders. The soil cracks or breaks up as it is rolled down to this diameter. Remolded soil at the plastic limit is quite stiff, having an undrained shear strength of the order of about 200 kPa.[4][10]

The plasticity index of a particular soil specimen is defined as the difference between the liquid limit and the plastic limit of the specimen; it is an indicator of how much water the soil particles in the specimen can absorb, and correlates with many engineering properties like permeability, compressibility, shear strength and others. Generally, the clay having high plasticity have lower permeability and also they are also difficult to be compacted.

Classification of silts and clays

[edit]

According to the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS), silts and clays are classified by plotting the values of their plasticity index and liquid limit on a plasticity chart. The A-Line on the chart separates clays (given the USCS symbol C) from silts (given the symbol M). LL=50% separates high plasticity soils (given the modifier symbol H) from low plasticity soils (given the modifier symbol L). A soil that plots above the A-line and has LL>50% would, for example, be classified as CH. Other possible classifications of silts and clays are ML, CL and MH. If the Atterberg limits plot in the"hatched" region on the graph near the origin, the soils are given the dual classification 'CL-ML'.

[edit]

Liquidity index

[edit]

The effects of the water content on the strength of saturated remolded soils can be quantified by the use of the liquidity index, LI:

When the LI is 1, remolded soil is at the liquid limit and it has an undrained shear strength of about 2 kPa. When the soil is at the plastic limit, the LI is 0 and the undrained shear strength is about 200 kPa.[4][11]

Relative density

[edit]

The density of sands (cohesionless soils) is often characterized by the relative density,

where:  is the "maximum void ratio" corresponding to a very loose state,

is the "maximum void ratio" corresponding to a very loose state,  is the "minimum void ratio" corresponding to a very dense state and

is the "minimum void ratio" corresponding to a very dense state and  is the in situ void ratio. Methods used to calculate relative density are defined in ASTM D4254-00(2006).[12]

is the in situ void ratio. Methods used to calculate relative density are defined in ASTM D4254-00(2006).[12]

Thus if  the sand or gravel is very dense, and if

the sand or gravel is very dense, and if  the soil is extremely loose and unstable.

the soil is extremely loose and unstable.

Seepage: steady state flow of water

[edit]